Solving three men’s morris FIFO version

I recently came across with this version (also called extended tic-tac-toe in Wikipedia) and wanted to try to make an AI to play against. I had created one in the past using minimax to solve the classic tic-tac-toe game so it would be a simple task (or so I thought).

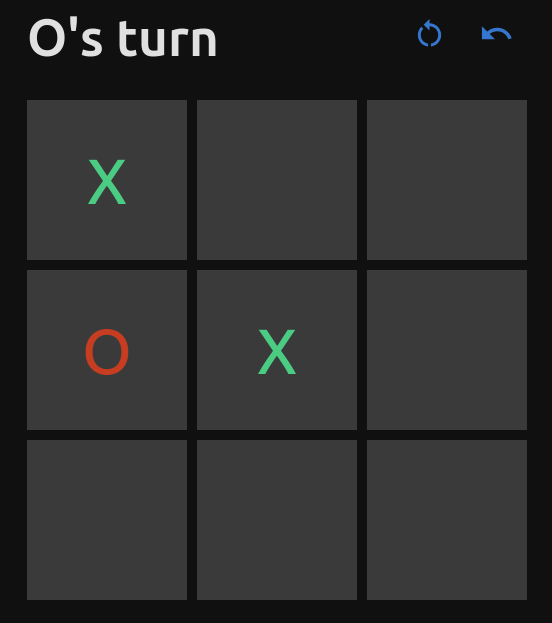

Before you continue reading this post, I suggest you play a couple of rounds to get familiar with the game: https://alijdens.github.io/three-tac-toe

The source code is available in Github: https://github.com/alijdens/three-tac-toe

Intro: Minimax

As mentioned before, classic tic-tac-toe can be solved by using minimax. We can model our game states and transitions as a graph that we walk is such a way that we find the most advantageous move for each player and propagate those decisions down to the initial state. For example, we can build a graph for the following state by enumerating the current player’s (X) possible actions and later the opponent’s (O) actions:

For simplicity, we'll represent states as circles throughout this post. Note that each level in the tree represents a player's turn and each edge is a possible choice for the next move.

We can treat the game states as a tree but that would make some branches to be repeated, making minimax need to explore much more states than actually needed. If we turn this into a graph where duplicated states are represented by the same node then we reduce the search by not processing the same state twice:

Note how we use a single node to represent the last state, which is obtained by following different paths from the beginning.

Tic-tac-toe is quite simple to solve: explore the graph of possible decisions and then pick the most convenient choice for the player in their corresponding turn. Propagate that decision backwards from the terminal states (i.e. win, draw or lose) until the beginning and then you’ll have an answer to whether a particular decision can lead to a victory, defeat or draw.

In the terminal states we would just set the score to:

- 1 if the maximizing player wins

- -1 if the minimizing player wins

- 0 if we reached a draw

Here’s a demonstration of minimax (use the Step button to advance the algorithm):

Terminal nodes (those without child states or output edges) have a score (which is determined based on whether the player would win, lose or tie). We propagate those scores backwards, choosing each turn the best option for each player. The green arrows represent the maximizing player's turn and the red ones the minimizer.

Differences with classic tic-tac-toe

If we add the new rule that the oldest piece placed in the board is deleted then we have a very important change in this logic: there’s no more draw (at least in the same sense as the classic game) because we will always have an available place to move but we can end up in an infinite cycle where each player just prevents the other one from placing 3 in a row (which we can consider a technical draw). In more mathematical terms, this means that we have now introduced cycles to the graph, which is a big problem if we want to apply the same logic as we do for classic tic-tac-toe. Consider applying minimax to the following graph:

If we navigate the graph, we'd never find a terminal node and so we would be cycling over it forever.

Another difference is that in tic-tac-toe we can derive from the board’s state which player’s turn is next. For example, if there are 3 X’s in the board and only 2 O’s, then it’s obviously O’s turn to play. Similarly, if there are the same number of pieces of both players then it’s X’s turn (assuming that X starts the game).

Finally, in tic-tac-toe we don’t care about the past: if we are in a particular state, it does not matter how we got there. However, it is important (up to some moves) for this variation because the order in which we placed the pieces affects how they will be deleted afterwards. This means that, although we might have the same squares filled with Xs and Os, we could be at 2 very different game states.

Note that even though both boards are similar they are not the same because the order in which the pieces will be deleted later is different.

First approach to solving cycles: DFS

My first idea to solve this problem was to DFS the graph until:

- a terminal state is reached

- a node that I have previously visited is reached again

In the terminal states we would just set the score to:

- 1 if the maximizing player wins

- -1 if the minimizing player wins

- 0 if we detect a cycle, which we considered as a draw

Note that a maximizing player will always prefer a draw to a loss (0 > -1) and so would a minimizing player (1 > 0).

If you attempt to DFS all the possible paths in the graph you’ll find out that it takes a very long time. There are 128170 different valid (non terminal) game states which have, on average, 3 out edges. Unlike traditional tic-tac-toe, whose graph is at most 9 nodes deep, the cycles create an almost never ending set of possible paths in the graph. To work around this I used a strategy to cache the values of already “solved” nodes so when I visit those again I can use the score I assigned before. This makes the algorithm run in a reasonable amount of time.

After implementing this algorithm I found that I could easily defeat the AI by playing a long enough game. Eventually, the AI would enter a state which was marked as a draw (score 0) but in reality allowed me to win (which even the AI found evident as many possible moves from there were marked as wins for me). Evidently, there was a huge problem in the draw detection algorithm.

At this point I started investigating the reason why this was happening and understood that the problem was that back propagating the draw score (0) to previous nodes could be misleading if that node didn’t end up in a real draw in the end. Consider the following example:

Notice how Node 14 is incorrectly labeled as a draw, even though it definitely leads to a victory for the minimizer. This tricks the maximizer into thinking that choosing that play will lead to a draw.

We can see in the example that the problem is partially labelling a path as a draw when we don’t actually know some other alternative path to the cycle leads to losing state. It may now be obvious that the answer to this problem is to first solve the paths that can force an outcome and then explore the other ones to effectively determine if the optimal play leads to a cycle.

Solution: Solving terminal states

We saw before that the problem is caused by assuming both players will stay on the cycle before actually checking if one of them could “break” it by choosing a more advantageous move that leads to a win. To work around this problem, we start by building the entire game graph and then move backwards from the terminal states, labeling all nodes that can force that outcome (like doing minimax but stopping when we don’t have a definitive answer):

- start by scoring all terminal nodes accordingly (+1 if maximizing player wins, -1 otherwise)

- put all the nodes that have an

inedge to those nodes into a queue - while the queue is not empty:

- take the next node

- if the node already has a score, skip

- if the player taking the decision that turn has a child that makes them win:

- score that node with the corresponding value

- append all parent nodes to the queue

- otherwise, if all child nodes do have scores:

- score that node with the children’s value

- append all parent nodes to the queue

by following the previous algorithm we will have all nodes that can force an outcome already cached, so we are ready to run the previous DFS logic and detect cycles.

By solving for the states that can force a win we can now label the states correctly.

If we inspect the scores of the choices available in the initial state (in the actual game’s graph), we’ll find out that the starting player can actually force a win! This is unlike tic-tac-toe where tow players playing optimally will end up in a draw.

Making the AI fun to play with

At this point I started testing the AI by playing against it and noticed that in some cases it was allowing very obvious losses (like it didn’t try). For example, I could be in the following situation:

and the AI would not try to block me from placing three in a row. This happens because (in some states) the AI knows that no matter what choice it makes the other player can always force a win. One interesting point about this is that the AI would be right if it happened to be playing an optimal opponent. This is however not true for most humans and so it’s very likely that they wouldn’t actually know that they can win, so the AI still has a chance if it makes the human player pick a wrong choice in the future.

Trying to force an error

So at this point, unless the player makes a mistake that can lead the AI to a draw or a win we’d get a series of random movements which are easy to beat. As mentioned before, it’s unlikely that the human knows how to win and it’s just exploring the game. This means that, even if we can’t force a win yet, we can still make the player’s path to a victory as slow as possible. We can calculate this by doing a slight modification to our algorithm: instead of using -1, 0 or 1 as scores we can use numbers that represent how close we are of a victory for the player.

For example, if we find ourselves in the scenario presented before (where the player can make 1 move to win), we’d assign a higher score to that position (for example 1) and lower scores to the rest (say 0.5 or 0.2). The minimizer would then pick the minimum score (0.2) which, even though it still leads to a loss, makes the player have to execute more perfect plays to reach the victory. On the other hand, if the minimizer player had as options [-1, -0.5, 0, 0.2, 0.8] then we’d pick -1 which should be the fastest path to a victory.

We can use the inverse of the number of steps to the victory (i.e. the number of nodes until the terminal state) as the score. For example, if have 2 paths, one that needs 3 moves and another that needs 10 to win, the scores would be 0.333... and 0.1 respectively. Note how the shortest path has the highest score.

AI intelligence levels

While developing the AI I thought it would be cool to add a setting to dumb it down. The way I chose to do this is the following: consider we are in some game state where some moves lead to a loss, some other to a tie or a win. As explained before, we can easily get the scores for each of those moves. Let’s image we are in the following situation:

Empty boxes show the (invented) scores calculated by the algorithm.

If we want the AI to play perfectly, then we can choose any of the 2 boxes with red scores (-0.25), which means that we’d win in 4 moves (remember that the score is the inverse of the number of moves until the end of the game: 0.25 = 1/4). We could “throw a coin” and select one of those based on the result. However, if we want the AI to make mistakes, we could introduce a small probability of it picking any of the other moves. Depending on how dump we want it to be, we could assign higher probabilities to worst outcomes. For example, we could assign 0.4 to each of the winning moves, 0.1 to the draw and the rest divide it to the losing scenarios (giving more weight to smallest values). The way I wanted the AI to behave was the following:

- if the intelligence is at it’s maximum value, then we’d assign equal probability to the best moves possible (following the previous example, we’d assign 50% chance to each of the moves with -0.25 score).

- if the intelligence is set to “dumbest”, then we’d assign uniform probability to all moves (i.e. play totally random).

One way to achieve this is to use the Softmax function to convert the scores to a probability distribution.

Softmax will assign more weight to larger values, so if we are playing the minimizer we’d have to multiply the scores by -1 to make those outcomes more probable.

The way in which we can favor moves can be by controlling the temperature. The temperature is a parameter that changes the distribution in the way we want: 0 temperature means that all the probability is concentrated in the largest value while higher numbers tend to distribute the values more evenly:

\[P_{i} = \frac{exp(score_i / T)}{\sum_j{exp(score_j / T)}}\]Softmax with temperature: the probability P assigned to move i will be the exponential of the corresponding score divided by the temperature, all of that divided by the sum of the rest.

For the game, I wanted to create a gradual change in the intelligence from 0 (dumb) to 100 (perfect player). The temperature changes the distribution very aggressively, so I had to create an intelligence factor which was converted to the temperature using a hand crafted function (by testing empirically) which was then plugged into the scores softmax:

\[T = e^{-intelligence \cdot 9} \cdot 45\]An example of a conversion of the intelligence factor into the temperature T.

Here’s an example of how the distribution would look like for the scores shown before:

Each bar represents a different move. The blue ones represent the probability assigned to that move and the gray ones show the score associated to that move. Try different intelligence values by moving the slider and see how the probabilities change.

Conclusion

Adding cycles to the game made it a bit harder to solve. While the algorithm described in this post finds the correct solution to the problem, traditional minimax can be used to calculate the best play at runtime (which is useful for games where we cannot pre-compute the whole graph). This algorithm requires the whole graph so it might not be usable in instances of the game where the grid is larger.

If you want to see the complete list of states and their score, you can check out the file containing them here.

Each key in the JSON object is a string encoding the game state (you can check out the explanation on how to interpret it here). We can use the JSON file to decide the best nex move by calculating the scores of the possible next states and then selecting the min or max (depending which player you are) among the possibilities.